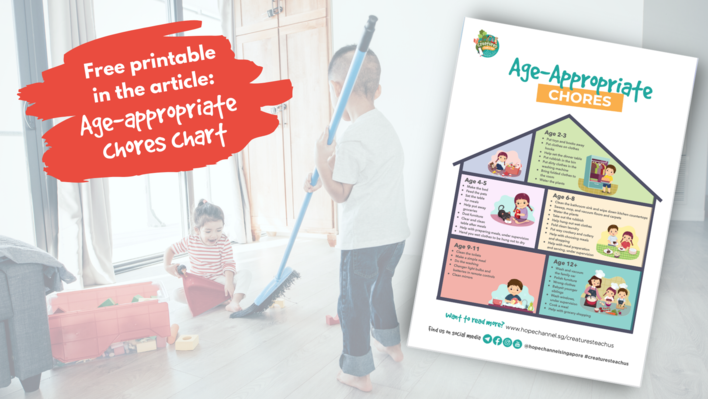

Get a free printable at the end of this article!

Kids who routinely help around the house are more likely to perform better at school, be emotionally stable and succeed in their professional lives as adults.

I used to think that household chores were just a natural part of life. When my parents did the grocery shopping, I would help bring the bags in. If Mum put a pile of dirty clothes in the washing machine, Dad or I would hang them out to dry. And if Mum decided to do some gardening, I would grab my little red watering can and follow her into the backyard.

Fast forward to high school. It was lunchtime, and I was walking across the main quad with a friend, blissfully unaware that she was about to drop a massive bombshell on me.

“I can’t go shopping this weekend,” she grumbled. “My parents haven’t given me money for doing the laundry yet.”

My ears pricked up. “You get money for doing the laundry?”

“Well, yeah,” she huffed before noticing the confusion on my face. “You mean you don’t?”

A quick survey of my other friends soon revealed that this particular friend wasn’t an anomaly. Some of my other friends also got paid for doing chores and a lot of them didn’t do chores at all.

“We have school and so much homework, so it’s not really fair for us to do housework as well,” another friend explained. I was so dazzled by her argument that I decided to try it out at home.

“I have piano lessons and Greek, so it’s not really fair that I have to do housework too . . . ” As you can probably imagine, that didn’t go down too well.

These days, however, I’m glad that my parents introduced me to chores from an early age. For one thing, research is on my side.

Kids who do chores are more successful later in life

If you’ve ever debated whether or not you should assign chores to your child, you might want to look up this US-based Harvard study, which is really two studies that ran simultaneously. The Grant study examined 268 Harvard graduates from the classes of 1939 to 1944 while the Glueck study consisted of 465 men who grew up in poor Boston neighbourhoods. Both studies observed the participants over a course of 75 years to see what variables and processes early in life could predict health and wellbeing later in life.

Two things were identified as essential for people to be happy and successful. The first, love. The second was work ethic. Researchers then determined that chores were the best predictor of which kids would become happy and successful adults. Children who were already accustomed to doing chores were more likely to take initiative, be able to work independently and adapt to difficult circumstances.

A 20-year study by the University of Minnesota in the US had similar results, finding that doing chores from the age of three is the best predictor for a good education, healthy relationships with family and friends, and also a good career.

“Involving children in household tasks at an early age helps them learn values and empathy as well as responsibility,” explains Dr Marty Rossmann, emeritus associate professor of family education at the University of Minnesota. “It is important for children to internalise values when they are young because household responsibilities continue to play a significant role throughout one’s life.”

Dr Marty goes on to point out that managing household responsibilities can be the biggest cause of stress in marriages, therefore children should learn these skills from an early age.

Marriage probably sounds pretty far away when you’re a child but Dr Marty makes a valid point. Many of the chores children are asked to do are the life tasks that they’ll need to survive one day. Nobody will ever pay you to empty your own rubbish bin or to vacuum your dusty carpet. If children don’t learn these skills when they’re young, how do they expect to cope when Mum and Dad are no longer around to do the heavy lifting?

How to get kids to do chores

According to American parenting and child development expert Dr Deborah Gilboa, children as young as 18 months old can and should get involved in household tasks such as sweeping with a brush and dustpan.

In 2014, appliance manufacturer Whirlpool commissioned a poll of 1001 parents. They found that 82 per cent of respondents grew up doing chores but only 28 per cent regularly assign chores to their own children.

When the parents who did assign chores to their own children were asked how their kids felt about their responsibilities, 43 per cent said they complained about them. 37 per cent tried to get out of them. And 13 per cent said their children would only do chores if they were paid.

It’s interesting to note that, although only 28 per cent actually assigned regular chores to their children, 75 per cent of the parents surveyed said regular chores made children more responsible and 63 per cent said that chores taught children important life lessons.

It seems that parents are preaching one thing and practising another. Parents want their children to be more responsible and successful in life, they believe that chores are an important factor in this, but they just don’t want to go through the process of arguing with their children over chores.

Here are a handful of hints to help your children get involved in doing chores.

1. Start young

Younger children (under six years old) are dying to be just like daddy or mummy and often offer to help. This is a golden opportunity. Use it. Some creative thinking may need to be involved: the task you’re doing may be dangerous or messy or perhaps you’re in a hurry and just know that involving your child will likely increase the mess quotient as well as taking longer. But try to find an aspect of the task that the child can safely do.

If you’re peeling potatoes for example, form a small production line and ask the child to take the rinsed potatoes out of the sink, shake them off and put them in a bowl. Little events like this through the week will blur the line between work and play and begin to build positive habits. It’s brainwashing, but in a good way!

2. Make it age-appropriate

Our free age-appropriate chores printable below will give you some ideas, but the premise is this: Begin with simple, safe tasks under supervision. For example, “Let’s put all the toys back in the toy box.” Look for opportunities for your young child to complete a short task without you in the room but let them know you’re coming back in just a minute to see if they’ve completed the task. But when a child is learning an age-appropriate task that involves a safety risk—cutting up fruit with a knife, for example—they should have close supervision. Hover at will.

Birthdays are one milestone that can be used to tell the child they’re now old enough to learn a new skill—to operate a lawn-mower, for example. In this way chores become a rite of passage and matter of pride for the growing child. Be prepared to flex a bit—you can pull back from allowing a child to do a particular task if they clearly don’t have the physical strength, coordination or maturity. You could also work alongside them for a bit longer than you originally envisioned.

While a younger child will need to be asked to help with a task every time, an older child can be expected to remember to do a particular chore every day or once a week—feeding a pet, for example. For primary aged children, a roster or chart is a fun way to remind them of their responsibilities. High-schoolers will probably respond better to an electronic reminder.

3. Keep it positive and relational

Use chores as an opportunity to affirm your child. Thank them for helping and tell them what a good job they’ve done. As they grow they’ll be able to appreciate more specific feedback; that they did a task quickly, thoroughly or with some extra loving details. If the positives are emphasised, the negatives will be less discouraging. Because, as children grow, the negatives need to be pointed out.

Don’t expect a learning child to get it right every time—you may need to give a little demonstration on the finer points, more than once. Avoid an exasperated response of, “For goodness sake, forget it; I’ll just finish it myself!” If you can work together to complete a task “properly” the child can enjoy the satisfaction of a job well done. You’re developing resilience—teaching your child how to deal with criticism—as well as having a bonding moment as you mentor your child in important life skills. Sticking at a task until it’s properly completed—including cleaning up afterwards—is a character attribute worth fighting for. Insist. They’ll hate you now; they’ll appreciate it later . . . possibly much later.

4. Keep it consistent and fair

Teaching your child self-discipline requires parental self-discipline. For older children, try to maintain a regular schedule of chores so that the expectations are clear. If the schedule is agreed together as a family and posted on the fridge for all to see it will be easier to enforce. There’ll also be less argument when penalties are applied for failure to complete chores. While we’re on that, try to make the penalties match the crime—”No dinner for you until the dog has had his dinner,” for example; “He goes hungry, you go hungry.”

Children often have a strong sense of justice; they’ll compare their chores with those of their siblings and notice (or imagine) differences in their respective responsibilities. Be ready with your reasons: “Because she’s younger”; “Because she also brings the bins in.” Or be ready to adjust the chores regime if your child has a legitimate point.

A child will often develop a dislike for a particular chore—they’ll hate it even more if they feel permanently saddled with it. One strategy is to swap chores from time to time—it deals with any niggling “not fair” complaints as well as teaching kids how to complete a wider range of household tasks.

Try to be aware of gender too: depending on your family background it may be easy to unconsciously identify certain chores as “boys’ jobs” or “girls’ jobs”. Try to avoid this. Every child deserves the opportunity to learn the full range of indoor and outdoor household skills—you never know what kind of living arrangements they’ll have as adults. You may also have to push yourself to lead by example; look at how the adults in the household divide the workload and, together, do your best to achieve a fair division of labour between the sexes. Otherwise, be prepared for some stern words from your household’s emerging feminist.

5. Keep it interesting

Most young children will participate readily in a job that has been creatively tweaked. Folding the laundry can become a guessing game: “Whose undies are these?!” And what’s not to like about The Sweeping Song—the one you just made up on the spot?

Older children will respond to competitions and challenges. If the stakes are heightened by the prospect of a reward or a looming deadline, so much the better—”If we can get the yard mowed and tidied by 11 o’clock we can go to the beach for a swim and an ice-cream!” [Hint: this strategy also works on parents.]

For regular daily chores a star chart is a good way for children to track their progress towards a goal—”Two weeks in a row of remembering to stack the dishwasher without being asked will earn you a trip to the movies!” Yes, this is dangerously close to a “chores for pocket money” scam, which is not a debate we’ll broach here. But let’s concede that sometimes a little extra motivation can go a long way, even if the reward is who gets the first turn of the X-Box when the chores are done.

Should you pay your children to do chores?

As Julie Lythcott-Haims says in her book How To Raise An Adult, having to fit in chores can help children learn how to manage time: “When they’re at a job, there might be times that they have to work late, but they’ll still have to go grocery shopping and do the dishes.”

Having kids do chores also models the important values of teamwork and respect. When children take on household responsibilities, they’re contributing to the wellbeing of the family as a whole and being part of a team. And you can’t scrub a dirty toilet once without feeling a healthy dose of appreciation for the person who does it most of the time.

Should you pay your children to do chores? That’s another question entirely. Some parents argue that it’s a good way to teach children financial independence and for them to learn how to value money. Others say that a weekly allowance could easily do the same thing.

Free Printable — Age-Appropriate Chores

Print out the chore chart, put it up on your fridge to remind you—and your kids—of the jobs they can do around the house.

This article is adapted with permission, from a version that was first published on Mums At The Table.